中華佛學研究所及學術的佛教徒

威廉.馬紀 老師

2003年我第一次飛抵台灣,感謝亦師亦友的傑弗瑞.霍普金斯教授引介,獲邀到中華佛學研究所展開一系列演講。原本我並不很清楚,應該對佛研所抱著甚麼樣的期待,但當車子第一次從海岸公路轉向法鼓山時,我感到內心深處的一股溫暖、安詳。我相信大多數人都會有同樣的感受,法鼓山是一個讓人感到溫暖的地方。2003時,山上除了高處的幾棟新建築物外,仍然非常的原始自然,但讓我感到安詳的是另一個原因,我喜愛觀世音菩薩的靈山聖地。

很久以來,我就覺得自己跟觀音菩薩,或西藏所稱的觀自在菩薩很有緣。我想不出人生有比修持觀音菩薩法門更有收穫的事。我曾到印度達賴喇嘛駐錫的山頂,品嚐慈悲的法水。接著,從美國被召喚到聖嚴法師的山上。離開台灣之後,我將前往澳大利亞,在卓巴喇嘛的觀自在學院停留六個星期,美好的因逐漸地結成果實。

當然,從沒有想到會在台灣待這麼多年;一直以來,我是一位周遊四方的佛法教師,僅與一些西藏佛教機構接觸往來。我曾經任教義大利的宗喀巴喇嘛學院,目前在中華佛研所,接著將前往澳洲的觀自在學院。我無法想像再回到穩定的學術教職。當我還是維吉尼亞大學的佛教學系的研究生時,覺得很快樂、充實。但畢業後在北卡羅來納大學分校擔任宗教學教師,卻讓我感到很空虛,那是一種沉浸於佛學之後的空虛。最後我逃離開,到美國西南部經營一所小型的多族群學校,但空虛感仍揮之不去。為了能再度沉浸在佛教中,我開始飛到世界各地從事教書與翻譯工作。我幫佛教出版社寫作,在維吉尼亞州的家裡跟家人度過快樂的幾個月,同時幫助傑弗瑞.霍普金斯把他收藏的大量藏傳佛學文獻轉成數位化。那段日子收入並不多,但生命完全沉浸在佛法中,並和觀世音菩薩產生特殊的法緣。

2003年,因著這個法緣來到佛研所。當時有兩位藏傳佛學組的學生被指定翻譯我講課的內容,講授的課題是中觀學派的佛教哲學。十多位師生聚集在五樓的大講堂,聽我談格魯派的空觀,那場聚會真是令人難忘,雖然和後來的發展相比,當時佛研所還只是小型研究機構。

與喇嘛相處愉快。

Bill and Loden Lama.

用午齋時,大家齊聚在宿舍地下室的齋堂(現在已是設備完善的健身房)。那時候我們人數還很少,如果不用午齋,必須先通知香積組。很難想像今天的法鼓山,是每天固定要提供好幾百位未先知會的臨時參訪者,在寬敞的大齋堂用齋。

在講課的那個星期,每次上完課學生們會陪我到研究所上方的山林走一大圈,經常可以感到佛研所學生對我既尊敬又好奇。我們會談到很多話題,其中學生們最感興趣的是:做為一位佛教徒,我是如何適應世間的學術氛圍。我能了解他們的問題,美國的佛教徒研究生也有相同的困擾。令這些學生們左右為難的是:佛研所是一所現代化的國際學術機構,具備高度的學術水準,但這些年輕的佛教徒不知道如何在成為一個學者所須具備的批判方法中,同時能夠調和自己的佛教信仰。

這也是我自己長久以來思考的問題。我認為佛教徒在大學裡有一席之地,就像其他信仰者有立足之地一樣。佛教徒不只是可以成為佛教學者,而且還可以擔當一個重要角色,透過所學將豐富的成果分享給宗教學以及相關領域,如歷史、哲學、人類學、藝術等的學生和教授。和一般學者同樣,進入學術界的關鍵是建立在扎實方法論的批判和客觀研究能力上,也唯有如此,我們的研究成果才會被學界其他人士出版、閱讀。

親和力十足。

Always encourage students to learn more.

荷西.卡貝松在〈佛學做為一個學科及其理論特色〉(《佛學國際協會》,第18-2期)一文,談到世界佛學研究中各式各樣誇張的刻板模式。他指出台灣的佛學研究往往被認為過於虔誠,當然就像所有刻板模式一樣,這樣批評非常不公平。不過,我也感到世界各地佛教徒學生這種過於虔誠的傾向。他們對佛陀的言教信仰是如此強烈,以致於忽視別人並不把這些深奧的言教視為理所當然的規範。對這種拘限自己研究的學生,我稱之為「規範式新聞寫作」。一個深陷於此窠臼的學生,閱讀經論只會照本宣科,這並不是真正的學術研究,沒有客觀的方法學做出的學術論文無法影響一般學界。如此一來,我們佛教徒將如其他宗教的傳教士被孤立一樣,孤立於學術界之外。如諺語「只對唱詩班講道」,我們無法分享所學,而只是被更強化宗教虔信的刻板印象。這樣佛法裨益人心的特質將如鴨背上的水一樣從學術界崩落,同時我們也錯失了傳達佛法價值的絕佳機會。

一個像家的地方—法鼓山。

Three friends at the DDM—Welcome Center.

我在法鼓山一週的停留很快就過去了。當講座結束,我打包好行李,下樓到車庫,準備前往機場時,不料竟看到學生們在那裡等著向我道別。他們要求我要再回來佛研所任教,我深深地被感動,並承諾如果可以的話我會回來;但內心卻覺得可能不會再有這樣的機會。除了我已經離開學術界外,還要飛往澳洲。接著,我在觀音菩薩的另座聖山,展開新的教書工作。我很喜愛澳州,但卻忘不了佛研所的學生們。

在此的過去一年,我的足跡遍及全世界,而現在我的旅行即將接近尾聲,迫切的想回自己的家。當我打開電腦查看電子郵件,出乎意料地發現一封來自佛研所邀約,請我擔任下一學年的教職。雖然實在不想跟妻兒們再分離那麼久,但另一方面我已經告訴學生們,有機會的話會回去,也跟他們說成為一個佛學研究者的重要性。於是我決定要留在台灣一年,就只一年,之後我就要回家安居了。

馬紀

2009年於法鼓山

與蒙藏委員會徐科長及霍普金斯教授。

With Mr. Hsi and Prof. Hopkins.

CHIBS and the Academic Buddhist

Bill Magee

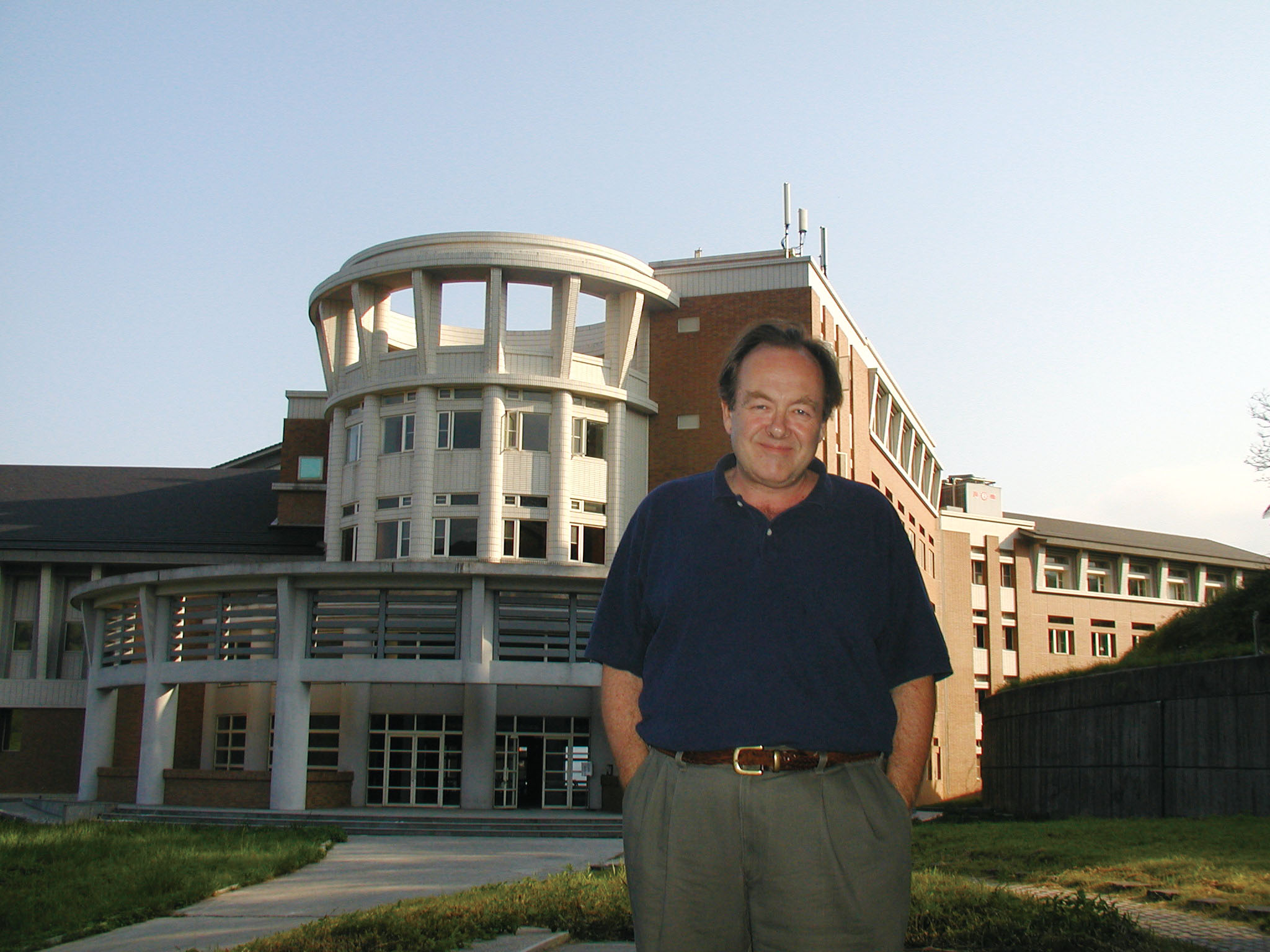

Bill Magee on DDM

In 2003 I flew to Taiwan for the first time. Thanks to the influence of my friend and teacher, Professor Jeffrey Hopkins, I had been invited to give a series of lectures at the Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies. I did not know exactly what to expect at CHIBS, but as I turned off the coast road and headed up Dharma Drum Mountain for the first time, I felt a warm and peaceful feeling deep inside.

I am sure that most people feel the same way. DDM is a heartwarming place. In 2003 it was still very much pristine nature except for a few new buildings at the very top. But my peaceful feeling had another cause: I love mountains sacred to the Bodhisattva Guanyin.

I have long felt a strong affinity for Guanyin – or, as she is called in Tibet, Chenrezee. I cannot imagine a more fruitful path in life than cultivating a connection with the Bodhisattva. In India, I traveled to the Dalai Lama’s mountaintop to taste the water of compassion. From America, I had been called to Master Sheng Yen’s mountain. Upon leaving Taiwan, I would be traveling to Australia, to spend six weeks at Lama Zopa’s Chenrezee Institute. Wholesome causes were coming to fruition.

Of course, at the time I had no idea I would spend so many years in Taiwan. In those days I was an itinerant dharma teacher, loosely affiliated with a few Tibetan Buddhist organizations. I had been in Italy, at the Instituto Lama Tsongkhapa. Now CHIBS. Next, the Chenrezee Institute in Australia. I could not imagine going back to a steady academic teaching job. As a graduate student in the University of Virginia’s Buddhist Studies program I had felt happy and fulfilled. But after graduation, teaching religious studies at a branch of the University of North Carolina left me with an empty feeling – a void where a life filled with dharma study had been. Eventually, I fled the University to run a small multi-ethnic school in the American Southwest: but the empty feeling stayed on. To reconnect with Buddhism, I began flying around the globe teaching and translating. I wrote for Buddhist publishers. I spent happy months at home with my family in Virginia while helping Jeffrey Hopkins digitize his extensive archive of Tibetan teachings. There was not much money in that sort of life, but it was a life involved with the dharma. My connection with Guanyin was being nurtured.

演講前由李志夫教授引言。

Prof. Lee’s Introduction.

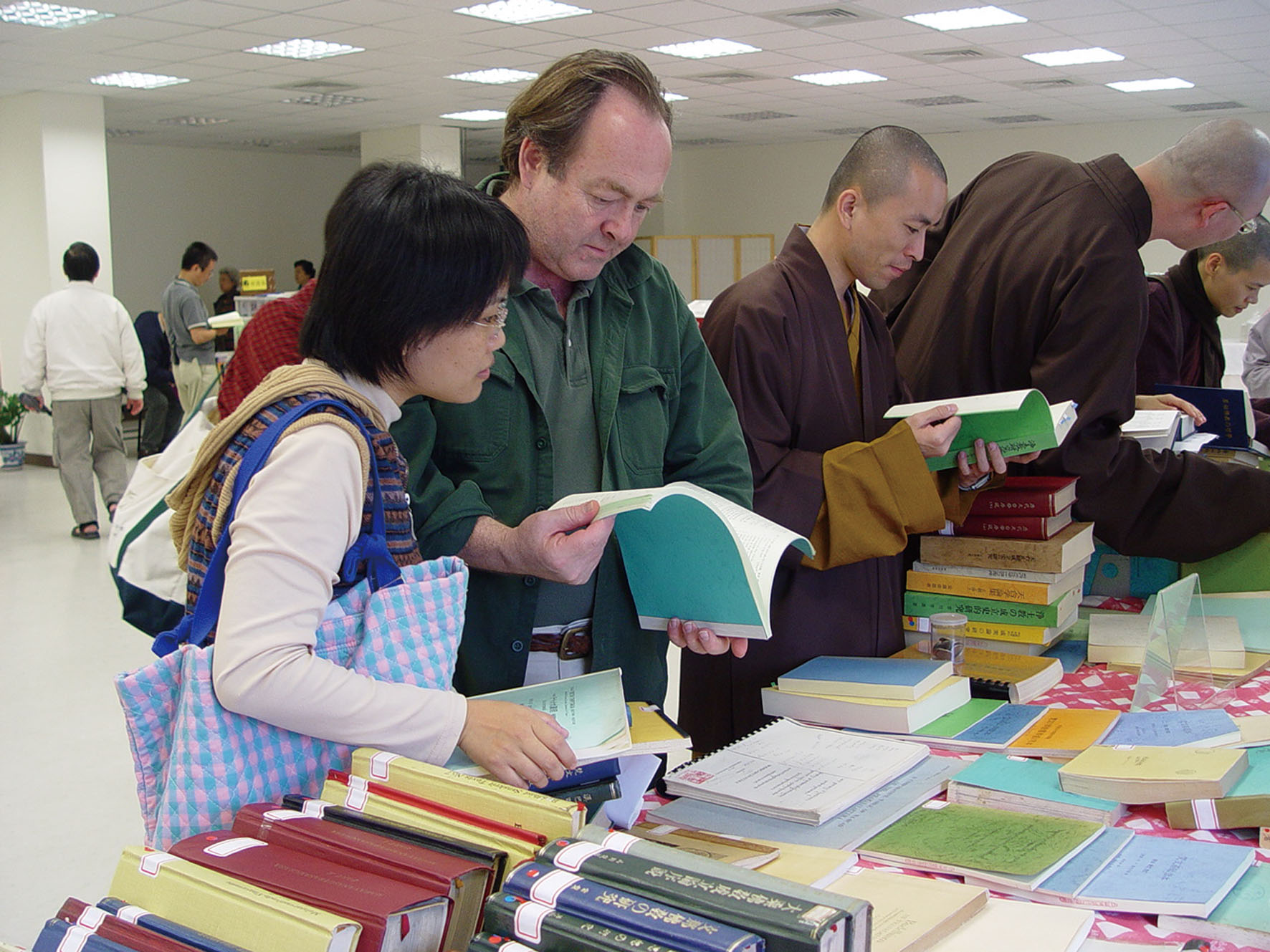

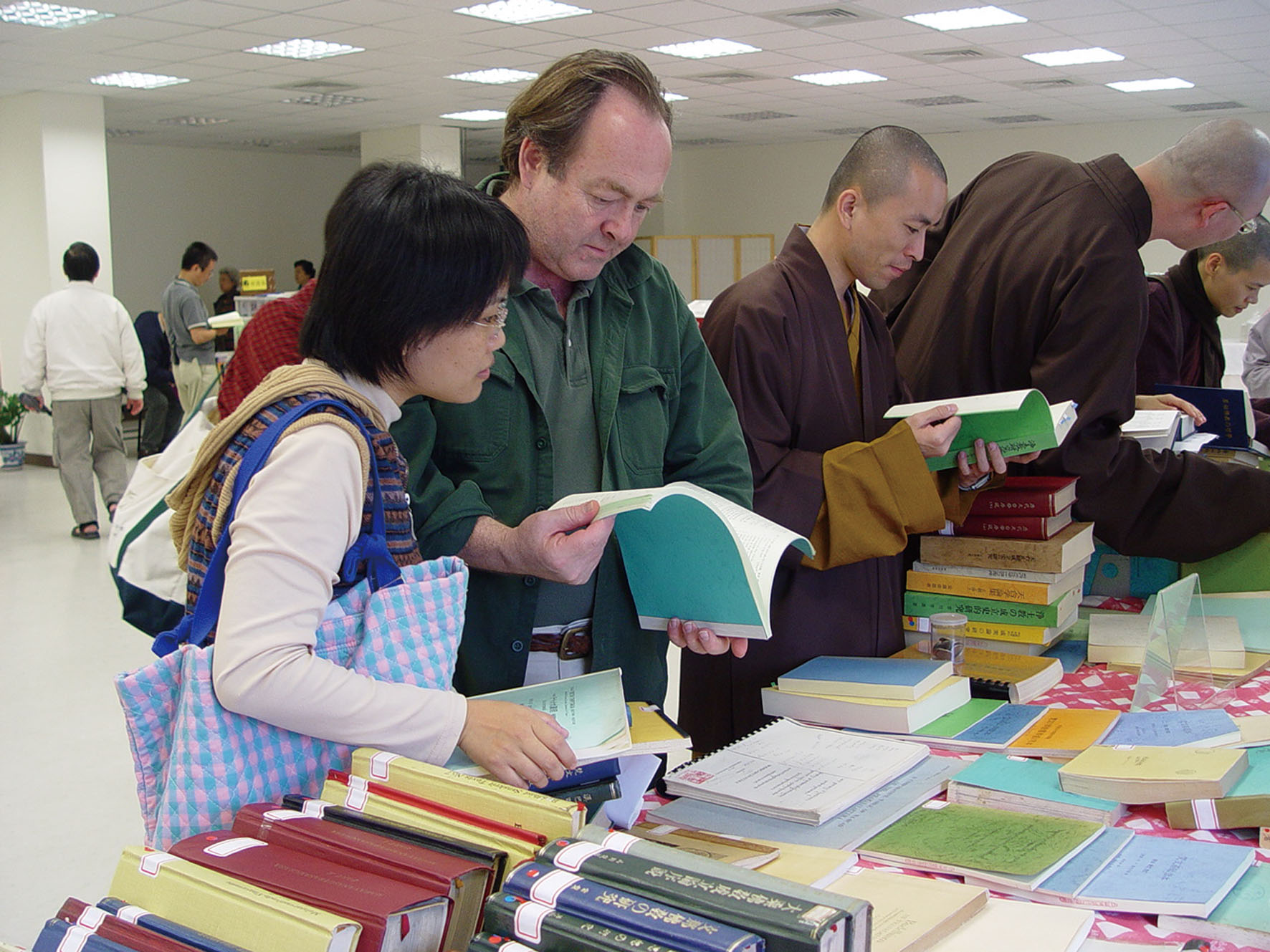

Two students from the Tibetan Studies program were assigned to translate my talks. My topic was the Madhyamika School of Buddhist philosophy. Over a dozen students and faculty assembled in the large lecture hall on the fifth floor to hear about the Gelugpa approach to meditation on emptiness. This was an impressive gathering: CHIBS in 2003 was a relatively small institute, compared to what it would become.

At lunch everyone adjourned to the dining hall in the basement of the dormitory (which today is a fully-equipped gymnasium). In those days there were so few of us that we were asked to notify the kitchen if we intended to miss lunch. This is hard to imagine on today’s Dharma Drum Mountain, which regularly hosts hundreds of unannounced visitors in its spacious dining halls.

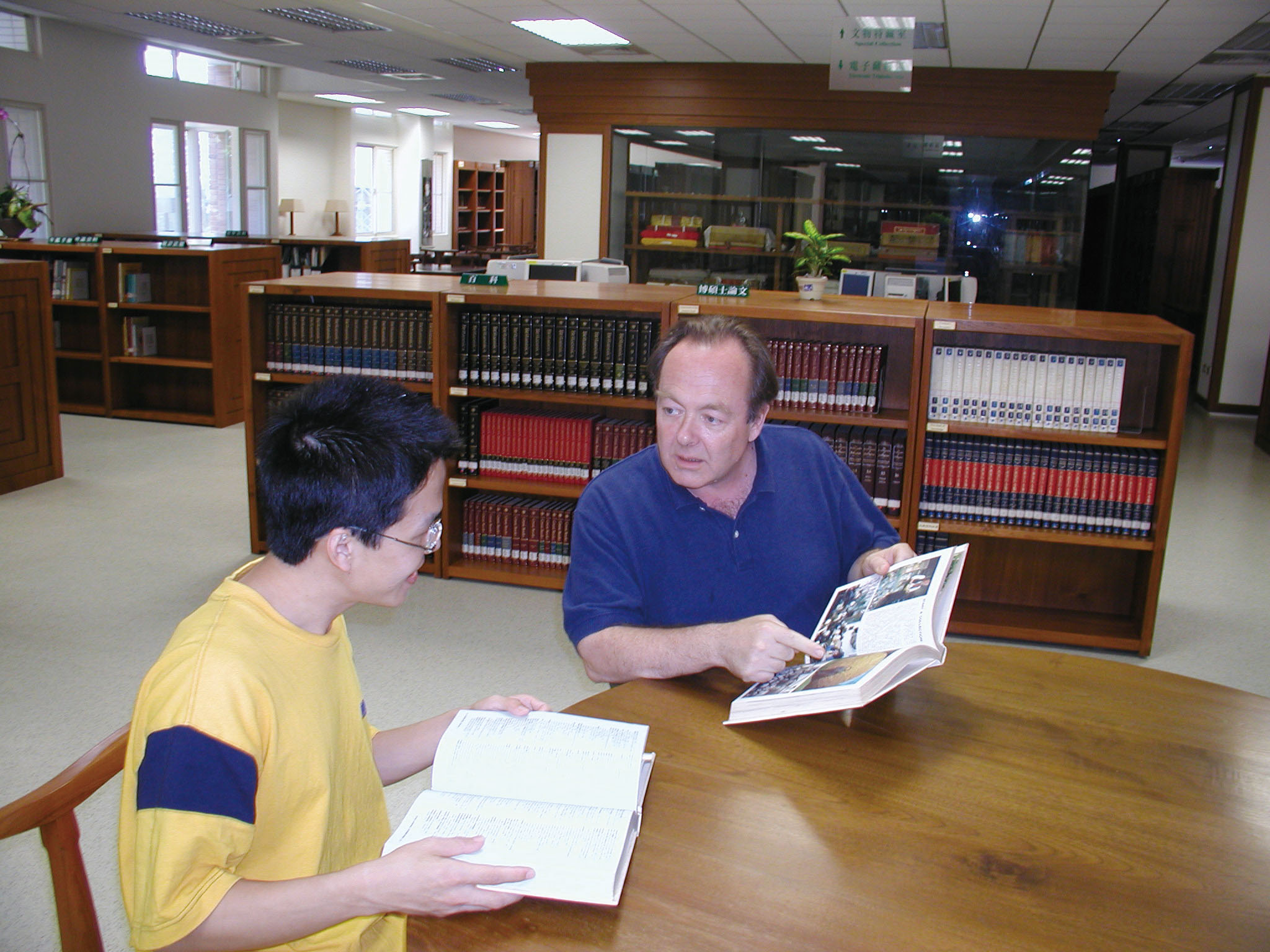

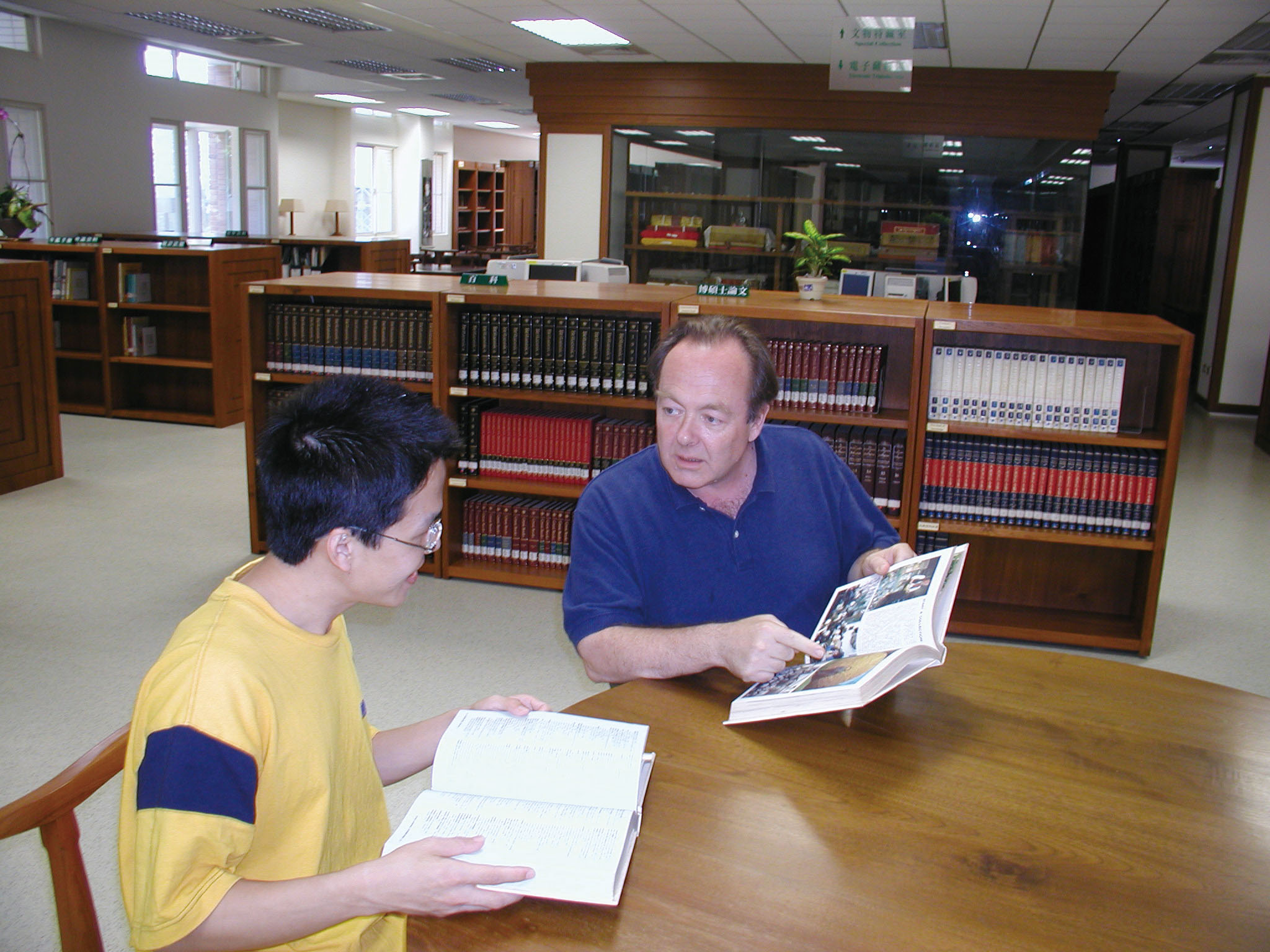

That week after classes I accompanied the students on long walks in the hills above the Institute. They treated me with a peculiar mixture of respect and curiosity that I have often seen in CHIBS students. We spoke of many things, but they were particularly interested in how I, as a Buddhist, fit in to the secular academy. I could understand their problem. I had seen it before, in American Buddhist graduate students. Their dilemma was this: CHIBS was a modern international academic institute, with high scholarly standards. These young Buddhists were unsure how to reconcile their faith in Buddhism with the critical approach required of a scholar.

This was something I had been thinking about myself. I pointed out that Buddhists have a place in the university, just as there is a place for people of other faiths. Not only is it possible to be a Buddhist academic, but it is an important role for us to fill. With our insider knowledge, we have much to offer students and professors in religious studies and related areas: history, philosophy, anthropology, the arts, and so forth. The key to entering into academia as the equal of secularists is the ability to undertake critical and objective research, based on sound methodological principles. Then, and only then, our research findings will be published and read by other academics.

為學生破疑解惑。

With the future Jamchen Lama .

José Cabezon, in his article, “Buddhist Studies as a Discipline and the Role of Theory” (Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 18.2) discusses a variety of caricatured stereotypes in the world of Buddhist studies. He points out that Taiwanese scholarship in Buddhist studies is often seen as pietistic. Of course, like all stereotypes, this one is grossly unfair. Nevertheless, I have seen this pietistic tendency in Buddhist students around the world. Their faith in the word of the Buddha is so strong that they neglect to remember that others do not view the profound teachings as normative. Such students confine their research to what I call “normative journalism.” A student involved in normative journalism reads the scriptures and commentaries and reports on their contents. This is not true scholarship. Without an objective methodology, our academic papers will have no influence in the secular academy. We Buddhists will become isolated from the academy, just as proselytizers of other religions are isolated. Preaching solely to the choir (as the saying goes), we will not be able to share our insider knowledge. We will only reinforce the pietistic stereotype. The wholesome predispositions of the dharma will slide off academia like water off the back of a duck, and we will have lost a golden opportunity to communicate its value.

與沙洛、袞確堪穌、馬天賜神父及李志夫教授。

Bill and Kenpo Konchok Tsering.

All too soon my week on Dharma Drum Mountain came to an end. Lecture series finished, I packed my bag and went down to the garage to depart for the airport. To my surprise the students were waiting to bid me farewell. They asked me to come back and teach at CHIBS. I was touched. I said I would return if I could, but in my heart I felt I would not have that chance. Besides, I had left the academy. And so I flew off to Australia. There I began another teaching job on another mountain sacred to Guanyin. I enjoyed Australia, but I could not forget the students at CHIBS.

During the past year I had been around the world; now my traveling was coming to an end. I was eager to return home to my family. I booted up my computer to check my email. There, to my great surprise, I found a letter from CHIBS offering me a teaching position for the next school year. I really did not want to spend more time away from my wife and children. But on the other hand I had told the students I would return if given the chance. I had also preached to them the importance of being a Buddhist academic. I decided I would spend one year in Taiwan. One year: 2003. After that, I would go home for good.

William Magee 2009 DDM